Cal Shakes is Pleased to Announce its First Scenic Intensive Training Course

as part of its Theater Workforce Development Program. June 17 – June 28, 2024 Approximately 40-60 hours of hands-on training Participants are paid $16/hour Participants

Reflections on the Solar Eclipse

By Philippa Kelly, Cal Shakes Resident Dramaturg These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us. Though the wisdom of nature

Terrapin Crossroads Announces Lineup for ‘Terrapin Roadshow’

First East Bay Terrapin Crossroads event to feature: Grahame Lesh, Dan “Lebo” Leibowitz, Stu Allen, Steve Adams, Alex Koford, Jason Crosby, and many more Special

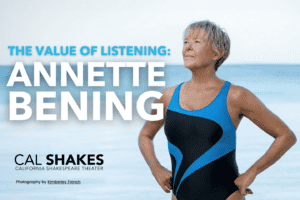

The Value of Listening: Annette Bening

(Update) In our excitement to celebrate Cal Shakes alum and Oscar nominee Annette Bening, we misspoke regarding one of her Cal Shakes credits – the

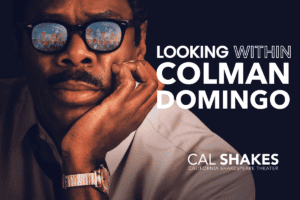

Looking Within Colman Domingo

“I think as artists, as actors, we are always watching. We’re watching heroes. We’re watching ordinary people do extraordinary things every single day. We’re watching

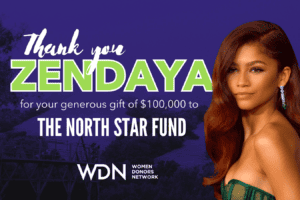

Zendaya and the Women Donors Network Donate $100,000 to the North Star Fund

Special thanks to Cal Shakes alum, Zendaya, for her $100,000 donation to the North Star Fund! Her support moves us forward in a big way toward